Network Analysis in Python

Contents

Introduction

Summary

This tutorial explores some basic network analysis in Python using the OSMnx and NetworkX packages.

First, a road network for Ottawa, Ontario is imported from OpenStreetMap (OSM) with OSMnx. The Nominatim API is used for geocoding - no external data download required. Then, shortest path examples are shown, first distance-based, then based on travel time. The incomplete nature of OSM datasets is explored in this section. Additional features such as creating n number of shortest paths, comparing routes, plotting with OSMnx, and exporting a route to a shapefile are shown. Finally, an example of the Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) is demonstrated.

This tutorial expects that the reader has at least a basic knowledge of Python.

Setup

Instructions for setting up a Jupyter Notebook with Anaconda and Google Colab are shown below. The only differences between the methods are found when installing the packages, exporting data, and the fact that geocoding seems to take somewhat longer with Google Colab.

Method 1. Anaconda

A Jupyter Notebook of this tutorial is planned to be provided in the future.

Download Anaconda here

Setup your Conda environment with the required packages by entering the following commands into Anaconda Prompt:

Create an environment

conda create -n network_analysis

Activate the environment

conda activate network_analysis

Install required packages

conda install -c conda-forge jupyter notebook osmnx

NetworkX, Geopandas, Pandas, and Numpy are all dependencies of OSMnx and will also be installed. Enter "y" for yes if prompted

Method 2. Google Colab

Add the following to the start of your notebook:

!pip install osmnx

NetworkX, Geopandas, Pandas, and Numpy are all dependencies of OSMnx and will also be installed.

Import Required Packages

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import geopandas as gpd

import networkx

import osmnx

Quick Review of Networks and Graphs

Basics

Networks are abstract structures that represent relationships between objects. Their applications vary widely, from social network analysis to neural networks in the brain, transportation planning, and stream network analysis. Graphs are used to represent and analyze networks mathematically.

Graphs are composed of two parts:

Nodes -> things or objects

- road intersections

Edges -> links or connections between nodes

- road segments

Edges can be directed or undirected (single or bi-directional).

Directed edges are useful for analysing stream networks, or in this tutorial for highways and one-way streets.

The study of the arrangement of nodes and edges in relation to each other, as well as in physical space, is known as Topology.

For more information, check out the Open Geomatics Textbook here.

Data Structure

Graphs, DiGraphs, MultiGraphs, and MultiDiGraphs are the data structures used by packages like OSMnx and Networkx.

- Graphs and DiGraphs represent simple undirected and directed graphs respectively. "Multi-" means that multiple parallel edges are allowed, like multiple lanes on a highway.

- Note: "parallel" in graph theory means that two edges connect Node A to Node B. This does not apply to bi-directional streets, since one connects A to B, and the other connects B to A, even though we would consider those lanes to be geometrically parallel.

The data imported in this tutorial is by default a MultiDiGraph, which suits the purposes of this tutorial.

For more information on the different graph data types, see the NetworkX documentation here.

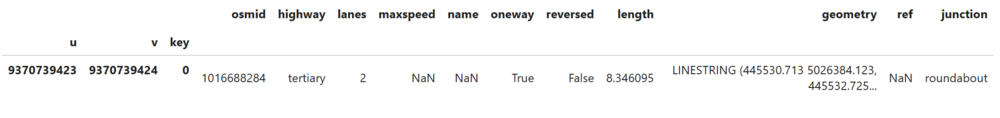

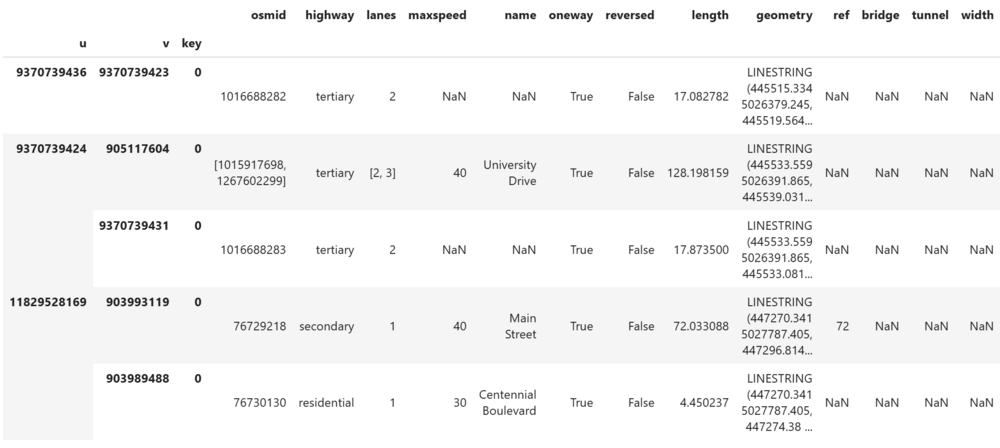

Indexing for Edges and Nodes

Throughout this tutorial, we will often be converting from MultiDiGraph to GeoDataFrame to explore the data. OSMnx converts a MultiDiGraph into separate GeoDataFrames for nodes and edges. Nodes use their OSM ID as their index, while edges use three indexes. The first ("u") and second ("v") show the OSM ID of the source and target nodes respectively, while the third index ("key") is used to differentiate multiple parallel edges. This tutorial does not use multiple parallel edges, so this key will always be 0.

Importing OSM Data

To explore some of the network analysis options in Python, this tutorial will use the road network of Ottawa, Ontario. This can easily be acquired using the OSMnx package, which uses Overpass API. The graph_from_place() function geocodes the area of interest (AOI) query and filters the network to the City of Ottawa's boundaries, while graph_from_polygon works with a custom polygon.

For additional information, check out the OSMnx documentation here and the example gallery here.

# create query for Smiths Falls

AOI = "Ottawa, Ontario, Canada"

# retrieve road network -> this may take some time

graph = osmnx.graph_from_place(

AOI,

network_type="drive" # this selects roads only. Other network options include "bike" and "walk".

)

# visualise the road network

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph)

Let's pick a smaller area that is easier to visualise. A geojson boundary is provided below, but can be replaced with any custom polygon.

# Downtown boundary -> this can be replaced with any geodataframe

ott_boundary_geojson = {

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"name": "ott_boundary",

"crs": { "type": "name", "properties": { "name": "urn:ogc:def:crs:OGC:1.3:CRS84" } },

"features": [

{ "type": "Feature", "properties": { "id": 1 }, "geometry": { "type": "MultiPolygon", "coordinates": [ [ [

[ -75.700646544981723, 45.442406206090276 ], [ -75.692602224956474, 45.439061352815521 ], [ -75.690143080492803, 45.436977332083586 ],

[ -75.686975368980271, 45.436893971254314 ], [ -75.684016059540923, 45.438561187839852 ], [ -75.679535414967276, 45.437998502242237 ],

[ -75.671449414527402, 45.433851300985694 ], [ -75.67046992478339, 45.42670310987517 ], [ -75.668531785502708, 45.424410687070051 ],

[ -75.667531455551384, 45.42140969721607 ], [ -75.663592656368039, 45.418596269227969 ], [ -75.663092491392362, 45.415928722691106 ],

[ -75.664426264660804, 45.414970073154414 ], [ -75.668406744258789, 45.414365707142153 ], [ -75.670657486649262, 45.413282016361556 ],

[ -75.672199661990902, 45.412219165788272 ], [ -75.673095790905634, 45.410072624434378 ], [ -75.668740187575892, 45.404154005555696 ],

[ -75.669865558771136, 45.400173525957719 ], [ -75.672783187795829, 45.397672701079401 ], [ -75.674429564174062, 45.3940048245912 ],

[ -75.678014079832991, 45.389128216078483 ], [ -75.689069809815834, 45.383136656474207 ], [ -75.695373972529922, 45.381729942480156 ],

[ -75.700063019176767, 45.378676852107873 ], [ -75.702199140426984, 45.378176687132189 ], [ -75.701886537317193, 45.381261037815442 ],

[ -75.700094279487729, 45.383803543108399 ], [ -75.700531923841439, 45.387554780425873 ], [ -75.70151141358545, 45.392181306450752 ],

[ -75.708805486147227, 45.396057585012137 ], [ -75.713369491550125, 45.403497539025139 ], [ -75.723758334898761, 45.410385227544161 ],

[ -75.725748574697747, 45.418075264044965 ], [ -75.70428316115887, 45.425369336606728 ], [ -75.700646544981723, 45.442406206090276 ]

] ] ] } }

]

}

AOI = gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(ott_boundary_geojson["features"], crs="EPSG:4326")

# retrieve road network -> this may take some time

graph = osmnx.graph_from_polygon(

AOI.geometry.iloc[0],

network_type="drive" # this selects roads only. Other network options include "bike" and "walk".

)

# visualise the road network

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph)

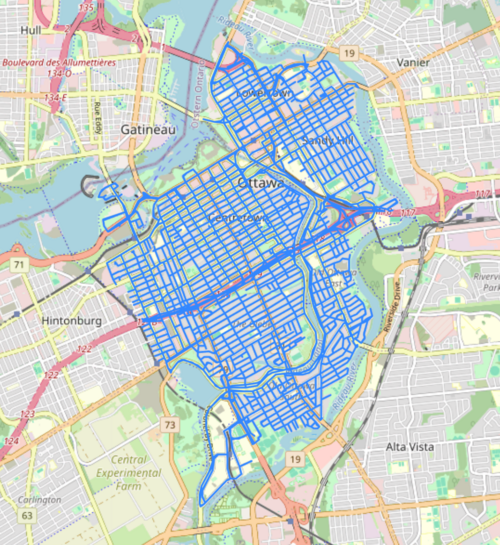

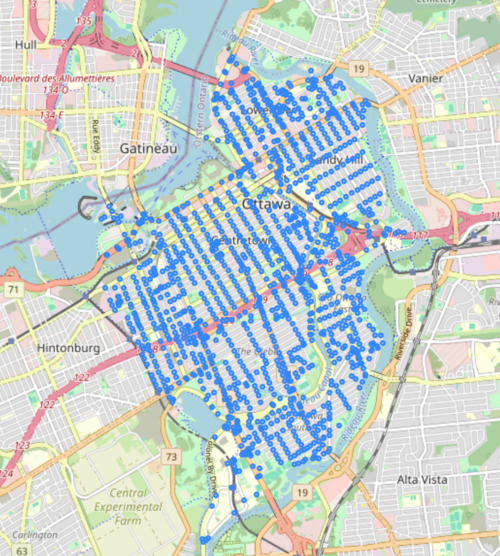

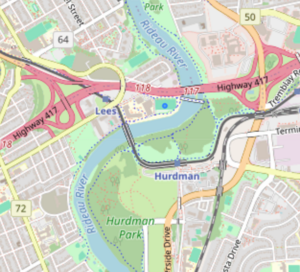

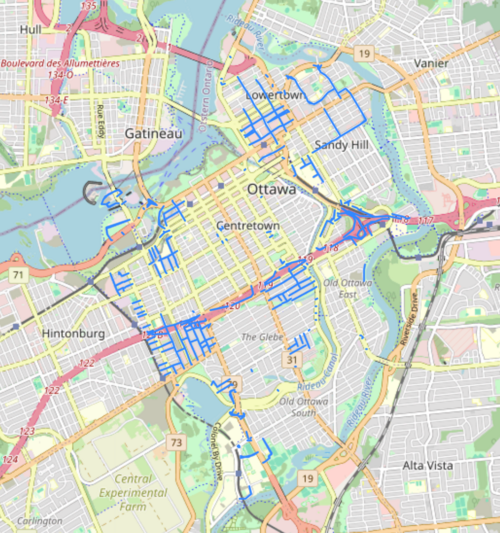

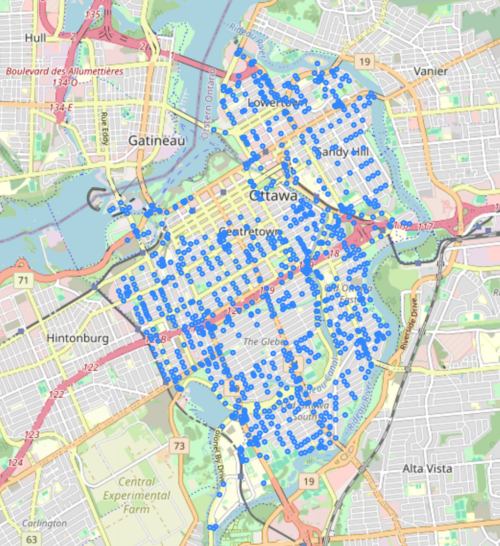

Let's examine the network with a basemap. We can do this by extracting the nodes and edges of the graph as geodataframes and using the .explore() method from GeoPandas.

# create geodataframes

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

# view edges with basemap

edges.explore()

# view nodes with basemap

nodes.explore()

Plot Customization

This looks good. Now let's customize some of the plotting parameters.

The configuration below can be easily applied as a base for any OSMnx plot we create later on.

Feel free to experiment!

Read the OSMnx documentation for further customization options.

# plot settings -> to be used as a base for most plots later on

pgr_args = {

"figsize": (8, 10), # figure size (width, height)

"bgcolor": "black", # background colour

"node_color": "black", # colour(s) of the nodes

"node_size": 5, # size(s) of the nodes

"node_alpha": 1, # opacity of the nodes

"node_edgecolor": "white", # colour(s) of the node borders

#"node_zorder" : 0 # this will plot nodes under the edges

"edge_color": "grey", # colour(s) of the edges

"edge_linewidth": 1, # line width(s) of the edges

"edge_alpha": 1, # opacity of the edges

}

# plot graph with new settings

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph, **pgr_args)

Projecting the Graph

Let's check the current coordinate reference system:

print(graph.graph['crs'])

epsg:4326

Data imported with OSMnx by default uses "EPSG:4326", which is the code for the WGS 84 Datum, a geographic coordinate system. For distance calculations, we need to use a projected coordinate system (x/y in meters).

Now we project the graph to the appropriate UTM zone and look at some basic statistics.

# project graph to UTM

crs = "EPSG:32618"

graph = osmnx.project_graph(graph, to_crs=crs)

# view basic statistics

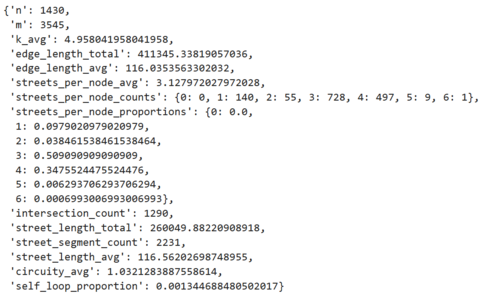

osmnx.basic_stats(graph)

This function shows some useful statistics about the graph. The first two lines show that there are 1430 nodes and 3545 edges. Note the difference between edge_length_total and street_length_total - remember that this a directed graph, with both single and bi-directional edges (roads). If every street was bi-directional, the the total street length should be exactly half of the total edge length. In this case, it is closer to 60%, which makes sense as Ottawa has a number of one-way streets and single direction highway ramps.

Check out the documentation for explanations of all the provided stats.

Simple Routing: Shortest Path

Let's explore one of the most basic applications of network analysis - determining the shortest path in the network between two nodes. This works the same way as a least-cost path analysis done on a raster, except with edges instead of pixels. A cost or weight is assigned to each edge, and an algorithm is used to calculate the path between two nodes with the lowest cumulative cost. OSMnx uses Dijkstra's algorithm.

See here more information on how Dijkstra's Algorithm works, as a great visualisation of how the algorithm works here.

For additional shortest path options not shown in this tutorial, see the NetworkX documentation.

Distance-Based

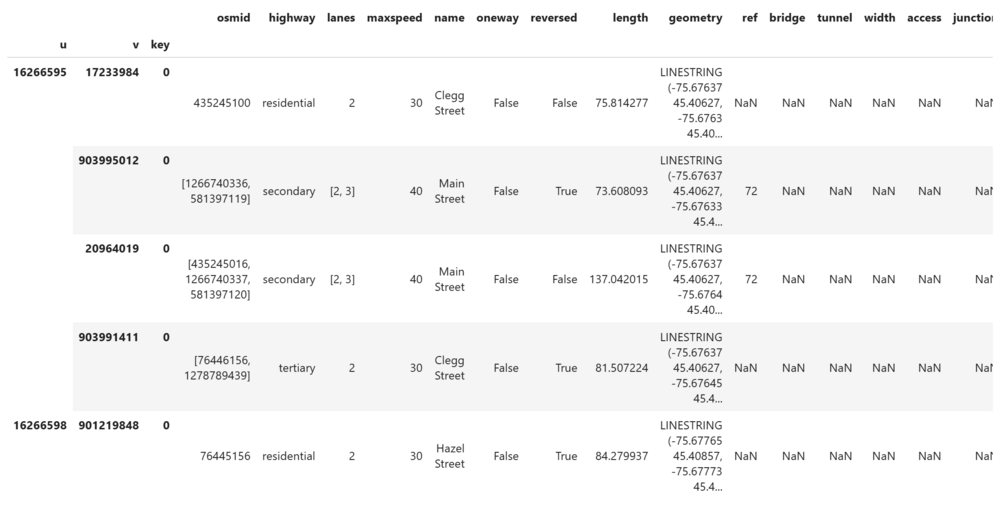

For a road network, the easiest cost or weight to use is distance. First, convert the graph into GeoDataFrames for nodes and edges. Exploring the edges geodataframe shows that distance is already present in the "length" column (this is done as part of the graph_from_place() function used earlier).

# extract gdfs

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

display(edges.head())

In this senario, a Carleton Student has just finished class and is going to pick up their friend from the athletics field at the University of Ottawa.

Let's define the start and end point using the geocoding functions in OSMnx. This can be done by simply querying the name of the building or place. However, it is not uncommon for the geocoding to fail, either because the feature is not present in the OSM data, or that the geocoding API requires that feature's name in a particular, sometimes unintuitive format. In this case, an address can be provided instead.

The geocoder outputs a geodataframe of the polygon feature (typically a building), but we need a point feature, so we take the centroid. It is also important to make sure that these new features use the same coordinate system as the graph.

# geocode start and end points, project to UTM and take centroid

start_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Carleton University, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

end_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Gee-Gees Field, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

We can quickly verify that the geocoding worked properly using the GeoPandas GeoDataFrame.explore() method.

start_point.explore()

end_point.explore()

Now we find the closest node in the network to the centroid points. This function outputs a list of nodes as it can be used for multiple input points, so the appropriate node IDs have to be converted to integers before proceeding.

# Find closest nodes

start_node = osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph, start_point.x, start_point.y)

end_node = osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph, end_point.x, end_point.y)

# convert to int -> for plotting

start_node = int(start_node[0])

end_node = int(end_node[0])

Let's determine the distance-weighted shortest path, with the weight set to the "length" column. The route can be plot using plot_graph_route, to which we can pass the plot configuration made earlier.

# Calculate a simple shortest path -> uses Dijkstra's Algorithm

route = osmnx.shortest_path(graph, start_node, end_node, weight='length')

# Plot the shortest path

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph_route(graph, route, orig_dest_size=100, **pgr_args)

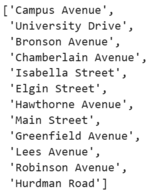

OPTIONAL: Extracting Street Names

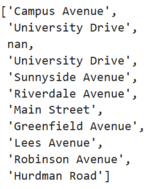

Now let's examine the roads taken by this route. The route_to_gdf() tool creates a geodataframe of only the edges traversed by this route. Because it is possible that the same road name appears multiple times, the aggregation must be done slightly differently than simply taking the unique names.

# create geodataframe of route

route_gdf = osmnx.routing.route_to_gdf(graph, route) # extracts edges used by route

# extract road names from

road_names = list(route_gdf.reset_index()['name'])

# aggregate road names

roads = []

for road_name in road_names:

if not roads or roads[-1] != road_name:

roads.append(road_name)

display(roads)

# filter edges in the route without street names

display(route_gdf[route_gdf['name'].isna()])

The "junction" column shows that this is part of a roundabout (the one by Carleton's main entrance), which doesn't have a street name in the OSM database.

Let's explore the edges that are missing street names in the whole network.

# filter edges in the graph without street names

no_names = edges[edges['name'].isna()]

no_names.explore()

As expected, they mostly comprise slip lanes and some driveways and can be ignored.

Time-Based

While distance-weighted shortest paths may be useful for walking or biking networks, travel time is often more important for driving routes. First, we need to calculate the edge speeds, or speed limits for every road segment. Then, the edge travel time can be calculated from the speed and length of each edge. Finally, intersection impedences can be added to approximate time costs for stop signs and traffic lights.

Side note: The osmnx.elevation module allows for edge grades to be calculated, which may be useful for calculating travel time in walking and biking networks, though this is not covered in this tutorial.

Add Edge Speeds

Edge speeds represent the maximum speed of a given edge, in this case the speed limit for driving on a given road segment.

Fortunately, the OSM data already contains speed limits for most road segments, stored in the 'maxspeed' column.

# 'maxspeed' stores speed limits

display(edges)

As seen previously with the roundabout missing a road name, the OSM data is not perfect.

Let's investigate the edges with missing speed limits.

# filter edges in network that are missing 'maxspeed' values

no_maxspeed = edges[edges['maxspeed'].isna()]

no_maxspeed.explore()

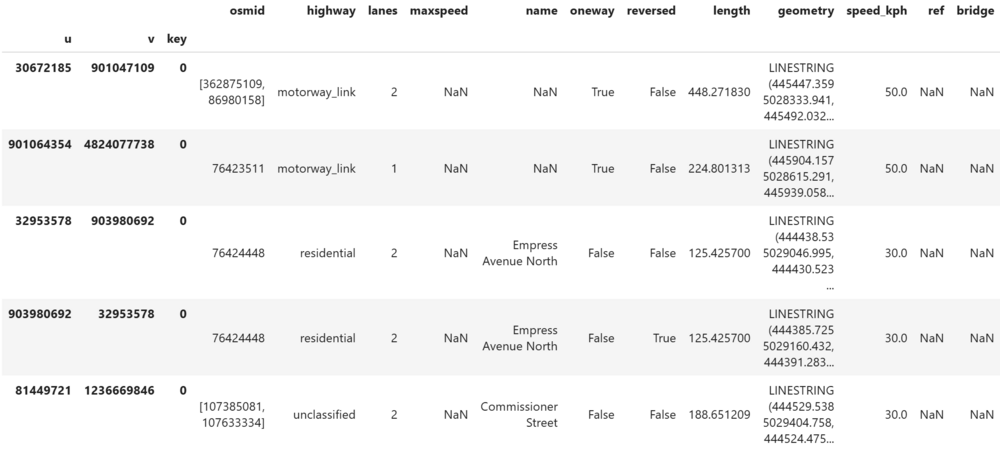

The edges missing edge speeds include lot of small residential streets, driveways, slip lanes, and some highway ramps. Some areas are clearly more complete than others. For calculating travel time, we need every road segment in the network to have an edge speed.

OSMnx has a useful function for generating edge speeds based on the road classification (OSM highway tag).

- For example, a street with the "residential" tag will be assigned a value equal to the median of all "residential" segments that do have an edge speed.

# generate missing edge speeds

graph = osmnx.routing.add_edge_speeds(graph,

hwy_speeds=None, # existing values of the same highway type will be used to generate the speed (can be replaced with a custom dict.)

fallback=40, # if a highway type is not found or recognized

agg=np.nanmedian) # median instead of mean to keep round numbers (30, 40, etc.)

# extract geodataframes again

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

# filter edges missing 'maxspeed' values

edges[edges['maxspeed'].isna()].head()

The 'speed_kph' column now contains any existing edge speeds from the 'max_speed' column as well as the values that were just generated.

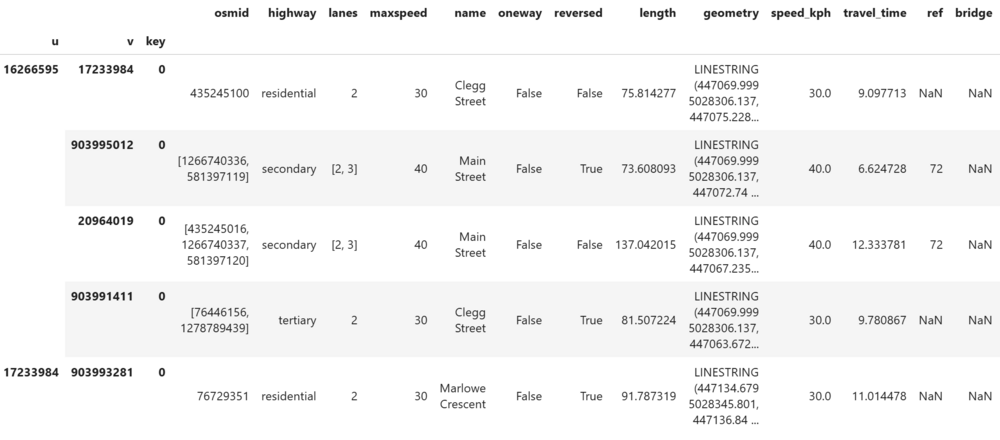

Calculate Edge Travel Times

This is a simple calculation using the speed limit and length of each segment. OSMnx has a useful function that automatically creates a new column "travel_time" with the time in seconds.

# calculate travel time

graph = osmnx.routing.add_edge_travel_times(graph)

# extract geodataframes

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

edges.head()

Add Intersection Impedances

The travel times we calculated earlier represent edge impedances, but there may also be impedances over nodes, especially in cities where there are many intersections with traffic lights. OSM uses tags to represent different types of intersections, so these can be used to generate average time costs at traffic lights and stop signs.

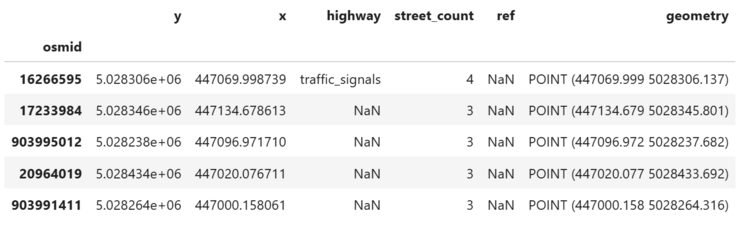

nodes.head()

It looks like a lot of nodes don't have tags. This makes sense, as not all nodes are intersections, and some intersections may not be signaled or signed. As we saw earlier with road names and edge speeds, the OSM data can be incomplete, so this warrants a closer look.

# calculate percentage of nodes without intersection data

print(len(nodes[nodes['highway'].isna()])/(len(nodes))*100)

# View of all nodes (intersections) without a tag (traffic lights, stop sign, etc.)

nodes[nodes['highway'].isna()].explore()

68.74125874125873

Almost 70% of the nodes in this area are missing a tag. Similar to the edge speeds, some areas are much more complete than others. While there was an easy way to fill in the missing edge speeds, there isn't a simple way to fix this issue, so unfortunately we will have to leave out intersection impedances from our time-weighted shortest path for Ottawa.

Time-Based Shortest Path

Let's try calculating the shortest path again, this time using travel time as the weight.

# Calculate a simple shortest path -> uses Dijkstra's Algorithm

route2 = osmnx.shortest_path(graph, start_node, end_node, weight='travel_time')

# Plot the shortest path

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph_route(graph, route2, **pgr_args)

OPTIONAL: Extracting Street Names

The second route takes a different path. Let's explore the road names again, but this time we can ignore any missing names, which we determined to only be slip lanes, driveways, and highway ramps.

# export road names from route

route_gdf = osmnx.routing.route_to_gdf(graph, route2) # extract this route's edges (road segments) from the larger network

road_names = list(route_gdf.reset_index()['name'])

# Because the same road name may appear multiple times, the aggregation must be done slightly differently than simply finding the unique names.

roads = []

for road_name in road_names:

if pd.isna(road_name): # ignore edges without road names -> highway ramps and slip lanes

continue

if not roads or roads[-1] != road_name:

roads.append(road_name)

display(roads)

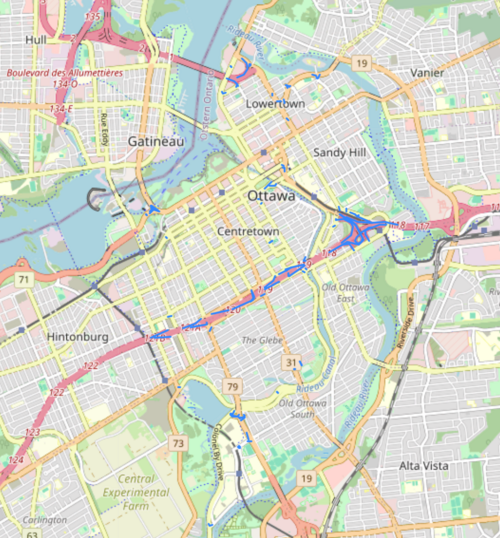

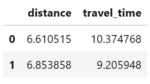

Route Comparison

Let's compare the paths visually and with some simple stats. plot_graph_routes() is a very similar function to what was used earlier, except it can plot multiple paths. Below, we will define a function to calculate the total distance and travel time for the two routes and present it in a dataframe.

# plot both paths

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph_routes(graph,

[route, route2], # list of routes

route_colors=["red", "blue"],

**pgr_args)

# Calculate distance and travel time

def routes_stats(list_of_routes, graph):

distance = []

travel_time = []

for route in list_of_routes:

edges_gdf = osmnx.routing.route_to_gdf(graph, route)

d = edges_gdf['length'].sum()/1000 # convert to km

t = edges_gdf['travel_time'].sum()/60 # convert to min

distance.append(d)

travel_time.append(t)

stats = pd.DataFrame({'distance': distance, 'travel_time': travel_time})

return stats

stats = routes_stats([route, route2], graph)

display(stats)

As expected, the time-based shortest path is slightly longer in distance, but is over 1 minute faster.

Exporting Routes

A commonly shown way to do this is to use only the nodes and create a LineString, but this won't account for curved road segments.

Instead, simply export the route gdf as a shapefile. If you would like the route as one geometry, use .dissolve() from GeoPandas.

For Google Colab users: This must be exported to your Google Drive, as shown at the end of this section.

# export as a Shapefile to disk

export_path = "C:\\NetworkAnalysisTutorial\\routes\\route2.shp" # replace with your path

route_gdf.to_file(export_path) # may get a warning about truncated column names. Rename them if desired

## FOR GOOGLE COLAB USERS ##

# mount drive

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive')

# export to Google Drive

export_path = "/content/drive/MyDrive/route2.shp" # replace with your path

route_gdf.to_file(export_path)

Multiple Shortest Routes

OSMnx can also generate a number of shortest paths. Let's try creating 20 shortest paths the same start and end points, using travel time as the weight.

# k shortest paths

routes = list(osmnx.routing.k_shortest_paths(graph, start_node, end_node, 20, weight='travel_time'))

# plot

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph_routes(graph, routes, route_linewidths=2, **pgr_args)

# Calculate basic stats

stats = routes_stats(routes, graph)

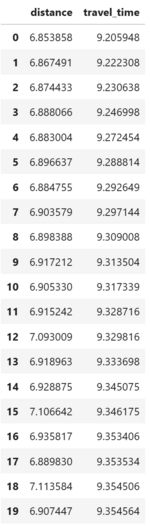

display(stats)

Travelling Salesman Problem

While OSMnx is useful for basic routing, more complex problems like the travelling salesman problem (TSP) require the NetworkX package.

For this example, let's imagine a person who is driving four of their friends home after a concert at the National Arts Centre. They would like to take the shortest possible route.

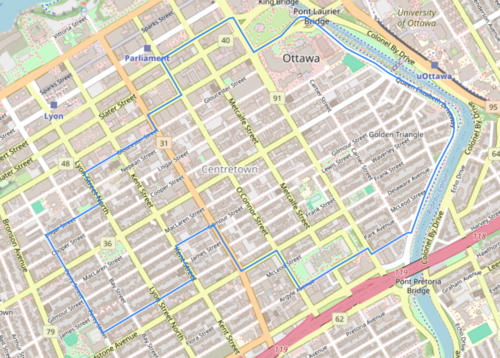

Since this is a computationally intensive problem, let's shrink the AOI down even more to keep processing times short. First, we have to truncate the road network for the boundary of downtown Ottawa provided below.

# boundary for downtown Ottawa

ott_boundary_small_geojson = {

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"name": "ott_boundary_smaller",

"crs": { "type": "name", "properties": { "name": "urn:ogc:def:crs:OGC:1.3:CRS84" } },

"features": [

{ "type": "Feature", "properties": { "id": 1 }, "geometry": { "type": "MultiPolygon", "coordinates": [ [ [

[ -75.702428219887494, 45.405001345279857 ], [ -75.711431189450465, 45.420786764941433 ], [ -75.700552601228551, 45.427661332829082 ],

[ -75.694821544215088, 45.424648327399943 ], [ -75.68977821404323, 45.422849223207727 ], [ -75.680796084687557, 45.41892902527232 ],

[ -75.680337600126478, 45.418065960065015 ], [ -75.683588672468687, 45.412623956986302 ], [ -75.683588672468687, 45.412623956986302 ],

[ -75.702428219887494, 45.405001345279857 ] ] ] ] } }

]

}

# convert to geodataframe

AOI_2 = gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(ott_boundary_small_geojson["features"], crs="EPSG:4326").to_crs(crs)

# truncate graph from previous examples

graph_2 = osmnx.truncate.truncate_graph_polygon(graph, AOI_2.geometry.unary_union)

# Visualise the road network

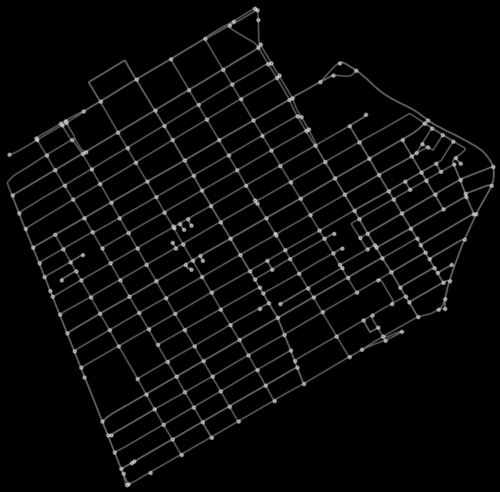

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph_2,

**pgr_args)

The TSP algorithm requires a strongly connected graph. This means that it must be possible to travel from any node to every other node in both directions.

Let's see if this is the case.

# check if strongly connected

print(networkx.is_strongly_connected(graph_2))

False

It looks like the graph is not strongly connected, so there must be some dead-end one-way streets or slip lanes in the network, which likely happened when the road network was clipped to the smaller AOI.

We can fix this by extracting only the largest strongly connected component.

# Remove weakly connected graph components

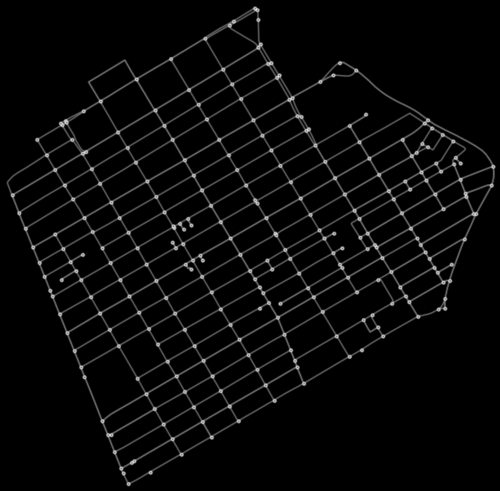

graph_2 = osmnx.truncate.largest_component(graph_2, strongly=True)

# Visualise the truncated network

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph_2, **pgr_args)

Let's check again if the graph is strongly connected.

# check if strongly connected

print(networkx.is_strongly_connected(graph_2))

True

If the previous process removes too much of the network, another option is to convert the graph to an undirected graph which is by nature strongly connected. This is more appropriate for walking and biking networks, where travel is almost always bi-directional.

#graph_2 = graph_2.to_undirected() # if truncating removes too much of the network

Now we can proceed with defining our starting point and three stops using a combination of place names and (random) addresses.

start = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("National Arts Centre, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

node_start = int(osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph_2, start.x, start.y)[0])

stop_1 = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

node_1 = int(osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph_2, stop_1.x, stop_1.y)[0])

stop_2 = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("180 Percy St, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

node_2 = int(osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph_2, stop_2.x, stop_2.y)[0])

stop_3 = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("715 Cooper St, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

node_3 = int(osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph_2, stop_3.x, stop_3.y)[0])

stop_4 = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("297 Bank St, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

node_4 = int(osmnx.nearest_nodes(graph_2, stop_4.x, stop_3.y)[0])

nodes_list = [node_start, node_1, node_2, node_3, node_4]

Using the TSP function from NetworkX, we use distance as the weight since travel time from speed limits aren't appropriate for bikes.

- Side note: OSMnx does offer tools for working with elevation values, meaning that travel time could be calculated from slope, but this is not included in this tutorial.

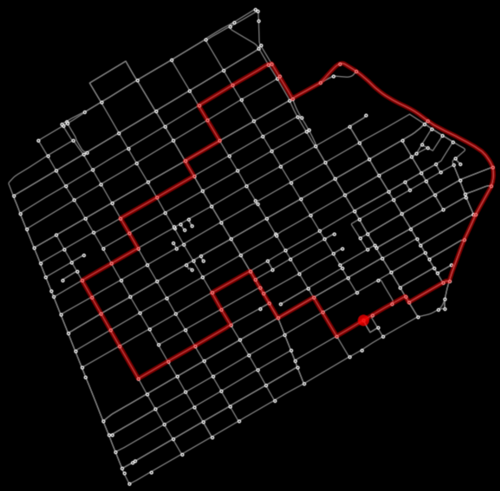

tsp = networkx.approximation.traveling_salesman_problem(G=graph_2, nodes=nodes_list, weight="weight", cycle=True) # this may take some time

# visualize

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph_route(graph_2, tsp, **pgr_args)

This route can be converted to a geodataframe and exported just like the previous examples

tsp_gdf = osmnx.routing.route_to_gdf(graph_2, tsp)

tsp_gdf.explore()

Conclusion

That concludes this tutorial on Network Analysis in Python.

References

OSMnx:

- Boeing, G. (2025). Modeling and Analyzing Urban Networks and Amenities with OSMnx. Geographical Analysis, 57(4), 567-577. doi:10.1111/gean.70009

NetworkX:

- Aric A. Hagberg, Daniel A. Schult and Pieter J. Swart, “Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX”, in Proceedings of the 7th Python in Science Conference (SciPy2008), Gäel Varoquaux, Travis Vaught, and Jarrod Millman (Eds), (Pasadena, CA USA), pp. 11–15, Aug 2008

GeoPandas:

- Kelsey Jordahl, Joris Van den Bossche, Martin Fleischmann, Jacob Wasserman, James McBride, Jeffrey Gerard, … François Leblanc. (2020, July 15). geopandas/geopandas: v0.8.1 (Version v0.8.1). Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3946761

Network Analysis with GIS:

https://www.opengeomatics.ca/network-analysis.html

A similar tutorial:

https://autogis-site.readthedocs.io/en/latest/lessons/lesson-6/network-analysis.html