Difference between revisions of "Network Analysis in Python"

| Line 242: | Line 242: | ||

=Simple Routing: Shortest Path= |

=Simple Routing: Shortest Path= |

||

Let's explore one of the most basic applications of network analysis - determining the shortest path in the network between two nodes. This works the same way as a least-cost path analysis done on a raster, except with edges instead of pixels. A cost or weight is assigned to each edge, and an algorithm is used to calculate the path between two nodes with the lowest cumulative cost. OSMnx uses Dijkstra's algorithm. |

|||

See [https://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs106b/cs106b.1262/lectures/27-dijkstra/ here] more information on how Dijkstra's Algorithm works, as a great visualisation of how the algorithm works [https://www.cs.usfca.edu/~galles/visualization/Dijkstra.html here.] |

|||

For additional shortest path options not shown in this tutorial, see the [https://networkx.org/documentation/latest/reference/algorithms/shortest_paths.html NetworkX documentation.] |

|||

1. Distance-Based |

1. Distance-Based |

||

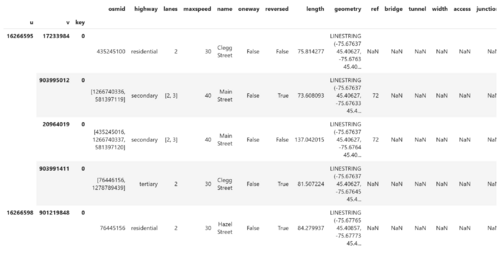

For a road network, the easiest cost or weight to use is distance. First, convert the graph into GeoDataFrames for nodes and edges. Exploring the edges geodataframe shows that distance is already present in the "length" column (this is done as part of the graph_from_place() function used earlier). |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python> |

|||

# extract gdfs |

|||

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph) |

|||

display(edges.head()) |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

[[File:7_show_length_col.png|500px]] |

|||

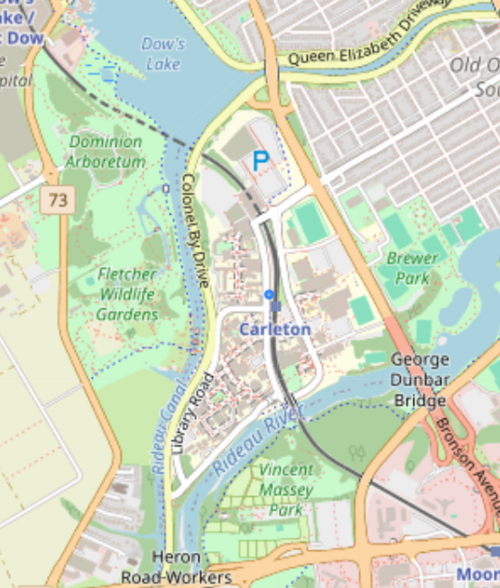

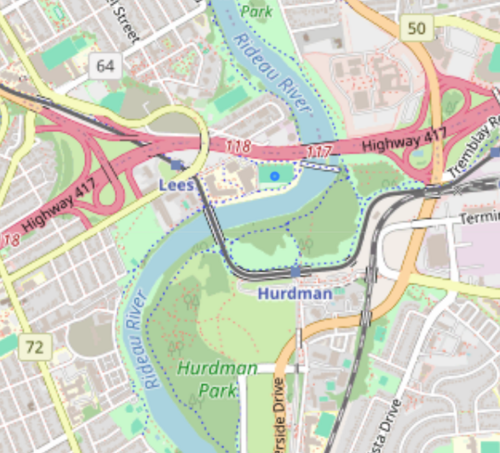

In this senario, a Carleton Student has just finished class and is going to pick up their friend from the athletics field at the University of Ottawa. |

|||

Let's define the start and end point using the geocoding functions in OSMnx. This can be done by simply querying the name of the building or place. However, it is not uncommon for the geocoding to fail, either because the feature is not present in the OSM data, or that the geocoding API requires that feature's name in a particular, sometimes unintuitive format. In this case, an address can be provided instead. |

|||

The geocoder outputs a geodataframe of the polygon feature (typically a building), but we need a point feature, so we take the centroid. It is also important to make sure that these new features use the same coordinate system as the graph. |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python> |

|||

# geocode start and end points, project to UTM and take centroid |

|||

start_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Carleton University, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid |

|||

end_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Gee-Gees Field, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

We can quickly verify that the geocoding worked properly using the GeoPandas GeoDataFrame.explore() method. |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python> |

|||

start_point.explore() |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

[[File:8_start_point.png|500px]] |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python> |

|||

end_point.explore() |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

[[File:9_end_point.png|500px]] |

|||

2. Time-Based |

2. Time-Based |

||

3. Route Comparison |

3. Route Comparison |

||

<syntaxhighlight lang="python> |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

=Generating Simple Directions for a Route= |

=Generating Simple Directions for a Route= |

||

Revision as of 04:55, 18 December 2025

Contents

Introduction

Summary

This tutorial explores some basic network analysis in Python using the OSMnx and NetworkX packages.

First, a road network for Ottawa, Ontario is imported from OpenStreetMap (OSM) with OSMnx. The Nominatim API is used for geocoding - no external data download required. Then, shortest path examples are shown, first distance-based, then based on travel time. The incomplete nature of OSM datasets is explored in this section. Additional features such as creating *n* number of shortest paths, comparing routes, plotting with OSMnx, and exporting a route to a shapefile are shown. Finally, a basic example of the Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP) is demonstrated.

This tutorial expects that the reader has at least a basic knowledge of Python.

Setup

Instructions for setting up a Jupyter Notebook with Anaconda and Google Colab are shown below. The only differences between the methods are found when installing the packages, exporting data, and the fact that geocoding seems to take somewhat longer with Google Colab.

Anaconda

A Jupyter Notebook of this tutorial is planned to be provided in the future.

Download Anaconda here

Setup your Conda environment with the required packages by entering the following commands into Anaconda Prompt:

Create an environment

conda create -n network_analysis

Activate the environment

conda activate network_analysis

Install required packages

conda install -c conda-forge jupyter notebook osmnx

NetworkX, Geopandas, Pandas, and Numpy are all dependencies of OSMnx and will also be installed. Enter "y" for yes if prompted

Google Colab

Add the following to the start of your notebook:

!pip install osmnx

NetworkX, Geopandas, Pandas, and Numpy are all dependencies of OSMnx and will also be installed.

Import Required Packages

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import geopandas as gpd

import networkx

import osmnx

Quick Review of Networks and Graphs

Basics

Networks are abstract structures that represent relationships between objects. Their applications vary widely, from social network analysis to neural networks in the brain, transportation planning, and stream network analysis. Graphs are used to represent and analyze networks mathematically.

Graphs are composed of two parts:

Nodes -> things or objects

- road intersections

Edges -> links or connections between nodes

- road segments

Edges can be directed or undirected (single or bi-directional).

Directed edges are useful for analysing stream networks, or in this tutorial for highways and one-way streets.

The study of the arrangement of nodes and edges in relation to each other, as well as in physical space, is known as Topology.

For more information, check out the Open Geomatics Textbook here.

Data Structure

Graphs, DiGraphs, MultiGraphs, and MultiDiGraphs are the data structures used by packages like OSMnx and Networkx.

- Graphs and DiGraphs represent simple undirected and directed graphs respectively. "Multi-" means that multiple parallel edges are allowed, like multiple lanes on a highway.

- Note: "parallel" in graph theory means that two edges connect Node A to Node B. This does not apply to bi-directional streets, since one connects A to B, and the other connects B to A, even though we would consider those lanes to be geometrically parallel.

The data imported in this tutorial is by default a MultiDiGraph, which suits the purposes of this tutorial.

For more information on the different graph data types, see the NetworkX documentation here.

Indexing for Edges and Nodes

Throughout this tutorial, we will often be converting from MultiDiGraph to GeoDataFrame to explore the data. OSMnx converts a MultiDiGraph into separate GeoDataFrames for nodes and edges. Nodes use their OSM ID as their index, while edges use three indexes. The first ("u") and second ("v") show the OSM ID of the source and target nodes respectively, while the third index ("key") is used to differentiate multiple parallel edges. This tutorial does not use multiple parallel edges, so this key will always be 0.

Importing OSM Data

To explore some of the network analysis options in Python, this tutorial will use the road network of Ottawa, Ontario. This can easily be acquired using the OSMnx package, which uses Overpass API. The graph_from_place() function geocodes the area of interest (AOI) query and filters the network to the City of Ottawa's boundaries, while graph_from_polygon works with a custom polygon.

For additional information, check out the OSMnx documentation here and the example gallery here.

# create query for Smiths Falls

AOI = "Ottawa, Ontario, Canada"

# retrieve road network -> this may take some time

graph = osmnx.graph_from_place(

AOI,

network_type="drive" # this selects roads only. Other network options include "bike" and "walk".

)

# visualise the road network

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph)

Let's pick a smaller area that is easier to visualise. A geojson boundary is provided below, but can be replaced with any custom polygon.

# Downtown boundary -> this can be replaced with any geodataframe

ott_boundary_geojson = {

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"name": "ott_boundary",

"crs": { "type": "name", "properties": { "name": "urn:ogc:def:crs:OGC:1.3:CRS84" } },

"features": [

{ "type": "Feature", "properties": { "id": 1 }, "geometry": { "type": "MultiPolygon", "coordinates": [ [ [

[ -75.700646544981723, 45.442406206090276 ], [ -75.692602224956474, 45.439061352815521 ], [ -75.690143080492803, 45.436977332083586 ],

[ -75.686975368980271, 45.436893971254314 ], [ -75.684016059540923, 45.438561187839852 ], [ -75.679535414967276, 45.437998502242237 ],

[ -75.671449414527402, 45.433851300985694 ], [ -75.67046992478339, 45.42670310987517 ], [ -75.668531785502708, 45.424410687070051 ],

[ -75.667531455551384, 45.42140969721607 ], [ -75.663592656368039, 45.418596269227969 ], [ -75.663092491392362, 45.415928722691106 ],

[ -75.664426264660804, 45.414970073154414 ], [ -75.668406744258789, 45.414365707142153 ], [ -75.670657486649262, 45.413282016361556 ],

[ -75.672199661990902, 45.412219165788272 ], [ -75.673095790905634, 45.410072624434378 ], [ -75.668740187575892, 45.404154005555696 ],

[ -75.669865558771136, 45.400173525957719 ], [ -75.672783187795829, 45.397672701079401 ], [ -75.674429564174062, 45.3940048245912 ],

[ -75.678014079832991, 45.389128216078483 ], [ -75.689069809815834, 45.383136656474207 ], [ -75.695373972529922, 45.381729942480156 ],

[ -75.700063019176767, 45.378676852107873 ], [ -75.702199140426984, 45.378176687132189 ], [ -75.701886537317193, 45.381261037815442 ],

[ -75.700094279487729, 45.383803543108399 ], [ -75.700531923841439, 45.387554780425873 ], [ -75.70151141358545, 45.392181306450752 ],

[ -75.708805486147227, 45.396057585012137 ], [ -75.713369491550125, 45.403497539025139 ], [ -75.723758334898761, 45.410385227544161 ],

[ -75.725748574697747, 45.418075264044965 ], [ -75.70428316115887, 45.425369336606728 ], [ -75.700646544981723, 45.442406206090276 ]

] ] ] } }

]

}

AOI = gpd.GeoDataFrame.from_features(ott_boundary_geojson["features"], crs="EPSG:4326")

# retrieve road network -> this may take some time

graph = osmnx.graph_from_polygon(

AOI.geometry.iloc[0],

network_type="drive" # this selects roads only. Other network options include "bike" and "walk".

)

# visualise the road network

figure, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph)

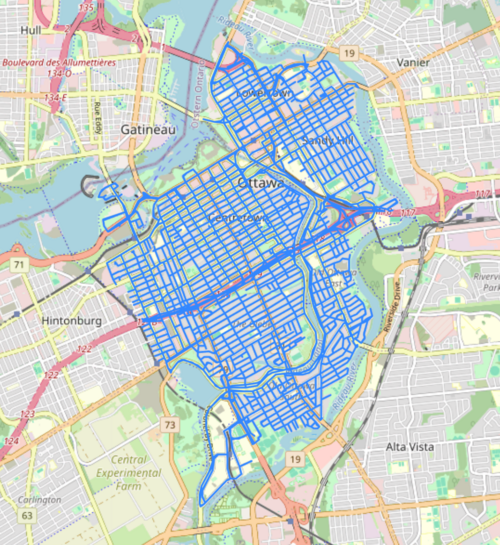

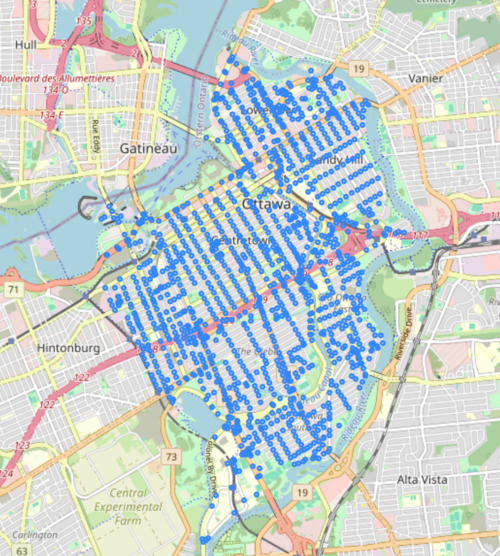

Let's examine the network with a basemap. We can do this by extracting the nodes and edges of the graph as geodataframes and using the .explore() method from GeoPandas.

# create geodataframes

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

# view edges with basemap

edges.explore()

# view nodes with basemap

nodes.explore()

Plot Customization

This looks good. Now let's customize some of the plotting parameters.

The configuration below can be easily applied as a base for any OSMnx plot we create later on.

Feel free to experiment!

Read the OSMnx documentation for further customization options.

# plot settings -> to be used as a base for most plots later on

pgr_args = {

"figsize": (8, 10), # figure size (width, height)

"bgcolor": "black", # background colour

"node_color": "black", # colour(s) of the nodes

"node_size": 5, # size(s) of the nodes

"node_alpha": 1, # opacity of the nodes

"node_edgecolor": "white", # colour(s) of the node borders

#"node_zorder" : 0 # this will plot nodes under the edges

"edge_color": "grey", # colour(s) of the edges

"edge_linewidth": 1, # line width(s) of the edges

"edge_alpha": 1, # opacity of the edges

}

# plot graph with new settings

fig, ax = osmnx.plot_graph(graph, **pgr_args)

Projecting the Graph

Let's check the current coordinate reference system:

print(graph.graph['crs'])

epsg:4326

Data imported with OSMnx by default uses "EPSG:4326", which is the code for the WGS 84 Datum, a geographic coordinate system. For distance calculations, we need to use a projected coordinate system (x/y in meters).

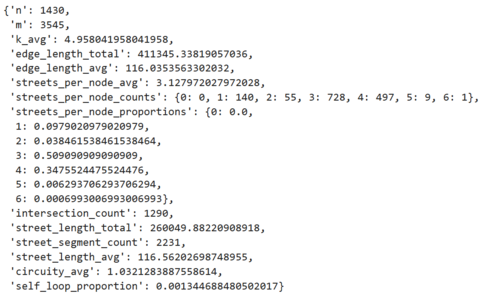

Now we project the graph to the appropriate UTM zone and look at some basic statistics.

# project graph to UTM

crs = "EPSG:32618"

graph = osmnx.project_graph(graph, to_crs=crs)

# view basic statistics

osmnx.basic_stats(graph)

This function shows some useful statistics about the graph. The first two lines show that there are 1430 nodes and 3545 edges. Note the difference between edge_length_total and street_length_total - remember that this a directed graph, with both single and bi-directional edges (roads). If every street was bi-directional, the the total street length should be exactly half of the total edge length. In this case, it is closer to 60%, which makes sense as Ottawa has a number of one-way streets and single direction highway ramps.

Check out the documentation for explanations of all the provided stats.

Simple Routing: Shortest Path

Let's explore one of the most basic applications of network analysis - determining the shortest path in the network between two nodes. This works the same way as a least-cost path analysis done on a raster, except with edges instead of pixels. A cost or weight is assigned to each edge, and an algorithm is used to calculate the path between two nodes with the lowest cumulative cost. OSMnx uses Dijkstra's algorithm.

See here more information on how Dijkstra's Algorithm works, as a great visualisation of how the algorithm works here.

For additional shortest path options not shown in this tutorial, see the NetworkX documentation.

1. Distance-Based

For a road network, the easiest cost or weight to use is distance. First, convert the graph into GeoDataFrames for nodes and edges. Exploring the edges geodataframe shows that distance is already present in the "length" column (this is done as part of the graph_from_place() function used earlier).

# extract gdfs

nodes, edges = osmnx.graph_to_gdfs(graph)

display(edges.head())

In this senario, a Carleton Student has just finished class and is going to pick up their friend from the athletics field at the University of Ottawa.

Let's define the start and end point using the geocoding functions in OSMnx. This can be done by simply querying the name of the building or place. However, it is not uncommon for the geocoding to fail, either because the feature is not present in the OSM data, or that the geocoding API requires that feature's name in a particular, sometimes unintuitive format. In this case, an address can be provided instead.

The geocoder outputs a geodataframe of the polygon feature (typically a building), but we need a point feature, so we take the centroid. It is also important to make sure that these new features use the same coordinate system as the graph.

# geocode start and end points, project to UTM and take centroid

start_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Carleton University, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

end_point = osmnx.geocode_to_gdf("Gee-Gees Field, Ottawa").to_crs(crs).centroid

We can quickly verify that the geocoding worked properly using the GeoPandas GeoDataFrame.explore() method.

start_point.explore()

end_point.explore()

2. Time-Based

3. Route Comparison